By Todd Smith

1. Introduction

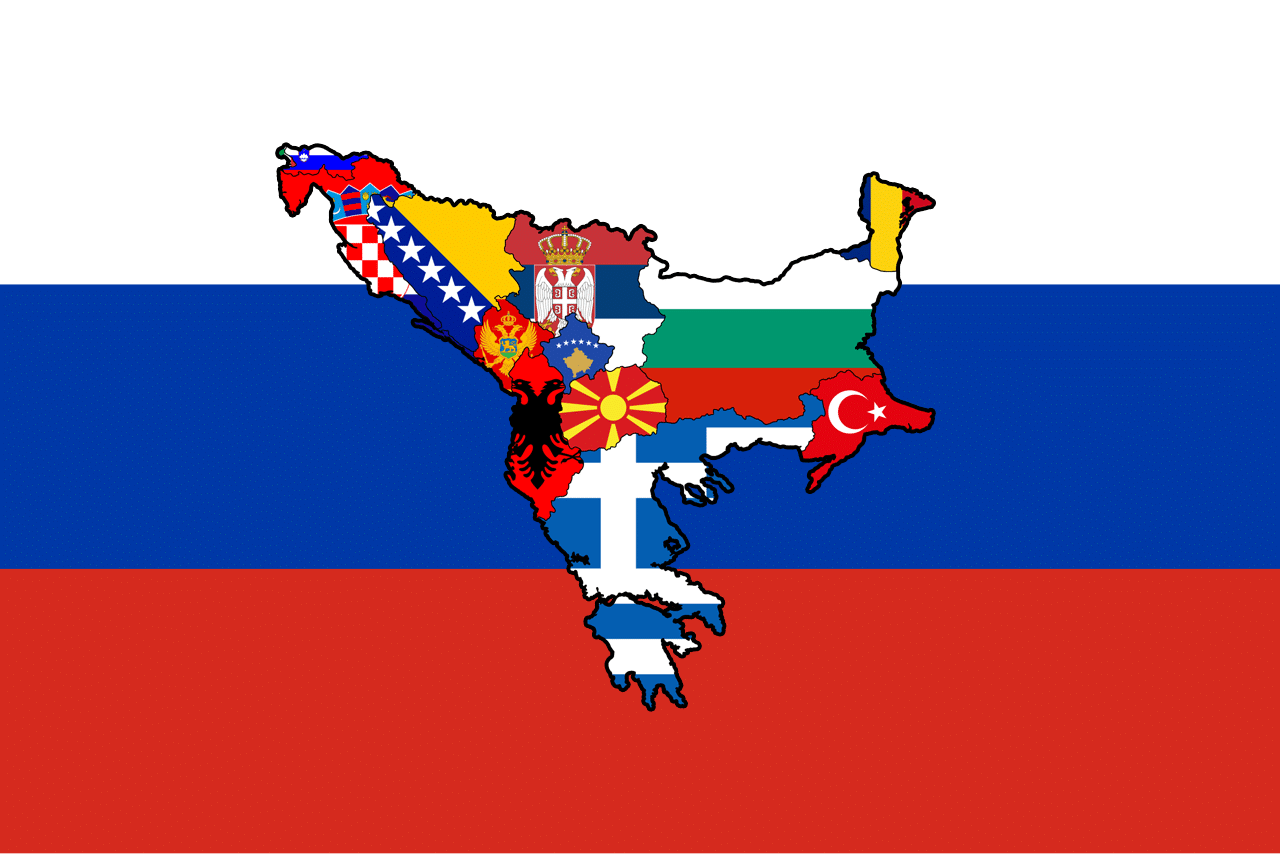

Following the Second World War, Albania underwent one of the most radical political, social, and cultural transformations in Europe. The establishment of a communist regime under Enver Hoxha after 1945 marked not merely a change of political leadership but a profound reconfiguration of Albanian society. This transformation was deeply influenced by Soviet Bolshevik ideology and reflected broader geopolitical strategies of the Eastern Bloc, particularly the Soviet Union’s long-standing ambition to extend its strategic and ideological influence toward the Mediterranean.

This study examines the argument that postwar Albania experienced a systematic process of cultural and social restructuring that aligned the country with Soviet–Slavic ideological models. Bolshevism functioned not only as a political doctrine but also as an instrument of social engineering, reshaping Albanian identity, dismantling traditional cultural foundations, and constructing a new ideological citizenry loyal to the party-state.

2. Geopolitical Context and the Ideological Framework

Historically, Russia lacked direct access to warm-water Mediterranean ports, a strategic limitation that shaped its foreign policy for centuries. After World War I and especially following World War II, this ambition was pursued through ideological rather than purely territorial expansion. The creation of the Soviet Union represented a strategic shift: ideology became a vehicle for influence where direct imperial control was no longer feasible.

In this context, Albania’s geographic position gave it disproportionate strategic importance. The postwar integration of Albania into the socialist camp reflected not only domestic revolutionary change but also the broader logic of Soviet geopolitical containment and expansion. Bolshevism, as implemented in Albania, should therefore be understood as part of an international ideological system rather than an isolated national development.

3. The Establishment of a Totalitarian State

After 1945, Albania rapidly adopted political, economic, and administrative structures modeled on Yugoslav and Soviet systems. Centralized planning, state ownership of land and industry, one-party rule, and strict ideological control became defining characteristics of the new state.

This transformation entailed a deliberate rejection of Albania’s prewar political pluralism and its cultural ties to Western Europe. The new regime positioned itself as revolutionary and progressive, while depicting traditional Albanian social structures as reactionary, backward, or ideologically dangerous.

4. The Assault on the Albanian Village and Traditional Society

One of the central pillars of Albanian identity had historically been the rural village. For centuries, particularly in mountainous regions, Albanian communities preserved language, customary law, and social organization with a high degree of autonomy. Scholars of Albanian society have emphasized that rural life functioned as a key reservoir of cultural continuity, relatively insulated from foreign domination.

The communist regime identified this autonomy as incompatible with socialist modernization. Through land collectivization, forced cooperatives, and population displacement, the traditional Albanian peasantry was effectively dismantled. The removal of private land ownership severed the organic relationship between the individual, the family, and the land—a relationship fundamental to Albanian social identity. This process resulted in the social disintegration of the rural world and the subordination of village life to centralized state authority.

5. Elimination of the Intellectual and Cultural Elite

Equally consequential was the systematic destruction of Albania’s pre-communist intellectual elite. Writers, scholars, clerics, and political figures associated with nationalist, religious, or Western-oriented traditions were marginalized, imprisoned, or eliminated from public life. Cultural memory was rewritten to exclude figures associated with the Albanian National Renaissance and earlier European-oriented intellectual traditions. In their place, the regime constructed a new ideological canon centered on socialist realism, revolutionary mythology, and political loyalty. Intellectual creativity became subordinated to ideological conformity. This pattern mirrored broader Soviet practices, where independent thought was treated as a threat to ideological unity.

6. Education, Culture, and the Soviet Model

Education and culture were reorganized according to Soviet pedagogical and aesthetic principles. School curricula, literature, music, and visual arts were required to adhere to socialist realism and to promote collectivism, class struggle, and loyalty to the party.

Western cultural influences—particularly modern music, literature, and philosophy—were censored or criminalized. Popular music genres such as jazz and rock were banned, while folklore was selectively institutionalized and reshaped to fit ideological narratives. Rather than serving as organic cultural expression, folklore became a state-controlled instrument of identity management. This process created a paradoxical cultural environment: while traditional culture was officially celebrated, it was simultaneously stripped of autonomy and redefined through a Soviet ideological lens.

7. The Construction of the “New Socialist Albanian”

At the core of the regime’s project was the creation of a new social type: the socialist citizen. This individual was expected to possess no private property, no independent cultural or religious identity, and no political autonomy. Loyalty to the party and the leader replaced loyalty to family, region, or tradition. Myth played a crucial role in this transformation. Revolutionary narratives, heroic symbolism, and the glorification of political violence were normalized as necessary components of socialist progress. The regime redefined moral values, presenting obedience, sacrifice, and ideological purity as the highest virtues. This model bore strong similarities to social organization patterns observed throughout the Soviet sphere.

8. Albania as an Ideological Outlier

Over time, Albania developed into one of the most isolated and ideologically rigid regimes in Europe. The extreme application of Bolshevik principles transformed the country into a highly controlled society, often compared to other closed socialist systems.

The cumulative effect of collectivization, cultural repression, and ideological absolutism produced a population disconnected from its historical social structures and increasingly dependent on the state for identity, security, and meaning.

9. Conclusion

Bolshevism in post-war Albania functioned as more than a political ideology: it operated as a comprehensive system of social and cultural transformation. Through the dismantling of traditional rural society, the elimination of intellectual pluralism, and the imposition of Soviet-inspired cultural norms, the Albanian state underwent a process of deep structural reorientation. This transformation aligned Albania’s social organization more closely with Eastern European socialist models, weakening indigenous cultural continuity and replacing it with an ideologically constructed identity. The legacy of this period remains visible in contemporary political culture, social behaviour, and institutional structures. Understanding this process is essential for interpreting both Albania’s twentieth-century history and its ongoing efforts to redefine identity in a post-totalitarian context.

ADDENDUM

The Slavicization of Albanian Culture in “Londonese Albania” within the Project of Nova Russia. The Creation of the Albanian State: Enveristan

Bolshevism represents a form of assimilation within the project of Nova Russia, whose objective was to secure access to the Mediterranean Sea, as Russia historically lacked access to warm-water ports. Albania became Stalin’s “gift” as a new Mediterranean port.

In 1945, a Serbo-Albanian illegitimate figure was installed in Albania. The child of a Bosnian Serb became the leader of Albania, brought to power by Yugoslav Serbs. He persecuted, killed, and executed the self-determination movement of pro-Western Albanians from Kosovo and northern Albania in exchange for an alliance with Yugoslav Serbs—his “brothers.” He betrayed everything Albanian, including communist ideologues from Kosovo and other Albanian lands. Enver Hoxha did not love Albanians. He had other plans.

In 1945, the Serbo-Albanian Enver Hoxha installed the Yugoslav currency, Yugoslav customs, accepted Serbo-Croatian language influence, and imposed a Russophile culture through Bolshevik methods as instruments of assimilation. Assimilation, annihilation, alibi politics, agitation, and escape from everything built as Western Albanian culture began. He imposed the Russian method to assimilate the culture of his own people.

For 2,000 years of occupation, every conqueror took Albanian cities, ports, rivers, plains, and seas. Albania was invaded hundreds of times. Yet no conqueror ever fully took the mountains, highlands, and inner plains. The highlands of Drenica, Rugova, and Shkodra remained incompletely occupied and retained their autonomy.

In his book “Kosovar Identity”, Mehmet Kraja precisely analyzes the Albanian village in Kosovo. The village preserved Albanian identity—pure Albanian identity—where neither the religion, culture, nor language of occupiers ever penetrated. People lived according to the traditions of Lekë Dukagjini, the Catholic Albanian prince and lord of these lands.

As noted by Milan Šufflay, the principal early Albanologue of the Balkans, these regions always remained Albanian in culture, language, tradition, and written Albanian wherever Catholic churches existed.

In 1945, the Serbo-Albanian from Gjirokastër, Enver Hoxha, attacked precisely the Albanian village—the same village where Milan Šufflay had begun studies of Albanian antiquity. The Serbo-Albanian dictator fabricated a war against “traitors” and “fascists,” exaggerating events in the name of alleged betrayal, annihilating ancient Albanian culture—the core source of Albanian identity—under the pretext of treason.

He eliminated the entire Albanian intellectual foundation in the name of Bolshevism, the new project of ideological Russification of peoples.

Bolshevik intelligence exploited southern Albania through the claim that it was allegedly closer to Russia than other Albanian regions. Balkan Russians infiltrated Albanian Orthodox priests through Russian agents disguised as clergy. Today it is known that Patriarch Kirill was a KGB agent; Ukrainians uncovered this. The KGB used sophisticated propaganda methods in the Balkans developed by Lenin and Stalin.

In Albania, an assimilative system was imposed through land collectivization—total deculturation of an agrarian society. In a land where Albanian identity had been preserved for centuries, the Albanian peasant was destroyed and dissolved. Enver Hoxha abandoned Albanian culture and absorbed Russian, Slavic civilization. He became socially Slavic, selling this as Bolshevism, socialism, and proletarianism.

Russia never abandoned Nova Russia after World War I; it merely changed strategy following the Treaty of Versailles by creating the Soviet Union. Communist Russia disliked the existence of multiple great European powers forming strategic alliances. The Soviet Union served to achieve two goals at once: perfecting ideology to control and Russify the Slavic world under the historical Pan-Slavic agenda—originally framed as liberation, not conquest.

Russia abused this concept and assimilated tens of millions of people, nearly assimilating Bulgarians by altering their language and alphabet.

During the 1800s–1900s, Russians assimilated Orthodox Albanians of the north and created the Serbian nation. These newly created nations committed genocide against Albanians because Albanians lived in mountainous regions resistant to assimilation. Russians acted similarly against Estonians and Finns, committing genocide when assimilation failed. The Russian Tsar nearly exterminated the Estonians; Stalin continued this policy. Stalin, a Georgian who became a Russian vassal under Bolshevik ideology, slaughtered entire peoples, including his own.

When Bolsheviks came to power, they formed a provisional government financed by the German Reich. Unable to persuade the masses, they accepted continuing Nova Russia under their format, later becoming the USSR. The Russian Church was integrated into intelligence as a demographic database. Clergy leaders were eliminated, leaving only ideological Bolshevik missionaries.

Stalin himself had once been a priest. Violent assimilation was applied to everything non-Russian. Ukrainians were starved by the millions as an assimilation instrument. Sixty million people were killed when assimilation failed except through bullets.

In 1945, Enver Hoxha applied this method in Albania. He assimilated Albanian society into Slavic culture.

He ordered the bones of Gjergj Fishta thrown into the river. What did Fishta do to deserve this? He sought to preserve Albanian cultural identity. Enver adopted myth as an instrument—myth being a Slavic tool for nation-building. Slavs built nations through myth. Enver copied this and constructed the “new Albanian” through myth, but unlike centuries-old Slavic myths, his lasted only years.

Enver normalized crime. In Slavic culture, crime is bravery. Killing one’s brother, sister, cousin, or friend becomes survival within Slavic myth. He legalized violence, betrayal, theft, smuggling, prostitution, and disobedience, redefining Albanian identity exclusively through Bolshevik Slavic-Russian ideology.

He destroyed the Albanian village—the genesis of Albanian attachment to the concept of property. Bolshevism mediated this rupture. By 1950, everything was decided at the Soviet Embassy in Tirana. Moscow governed Albania’s daily politics; the Soviet ambassador functioned as king and governor.

Enver believed Albanians could not survive without collective material control. Bolshevik commissars were installed in Tirana. Russification intensified. The socialist Albanian had no land—only the party and Enver, myth and glorification, deception and crime. Schools, culture, music, art, and literature became entirely Soviet Bolshevik Slavic. Slavic culture became fashionable. A new Albanian identity was created through Bolshevik Nova Russia methods.

Western intelligence documents describe Enver as a strange man with a dubious past. He was Serbia’s man from the beginning. Russia now had its Russophile in Tirana. Albania remained under his control. Western plans for a large Euro-Atlantic Albanian state were disrupted. Enver intensified repression against pro-Western Albanian intellectuals. In Albania, Enver massacred Albanians; in Yugoslavia, Tito massacred Albanians through killing and deportation.

Enver interned everything Albanian and created a new nation—Enveristan. Albanian society was Slavicized. Albanian citizens were permitted cultural expression only through Slavic-approved folklore. Western music was banned. Folk ensembles were funded to prevent Western influence such as jazz, rock, and blues. Albanian composers creating Western music were imprisoned or killed.

The “new Albanian” became Bolshevik—thus Slavicized in consciousness which manifested within the mores of social organisation. Enver believed Albanians could survive only through Bolshevism, transforming Albania into the “North Korea of Europe.” He detached Albanians from land, home, and identity. Anyone loyal to Enver was no longer Albanian—he was Enverist, living in Enveristan.

Analyzing today’s Albanian politics and general state of affairs, reveals similarities to Eastern Slavic political culture. Enver Hoxha succeeded in Slavicizing Albanian social organization. Bolshevism was one step away from the assimilation of Albanians into Slavs.